This week’s stock market blood bath caught many by surprise.

I’ve heard many call it a Black Swan.

What is a black swan? According to Nicholas Taleb, the author of “The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable” they are events/ideas/movments/etc. defined by three traits:

- First, they are an outlier

- Second, they carry high consequence

- Third, despite being outlier events we tend to create explanations for their occurrence after the fact, making them plausible/explainable/predictable

There are wide ranges of unpredictable events/products/movements that can all be considered Black Swans. Examples are:

- Wars

- Religious movements

- The computer

- The internet

- The Harry Potter craze

- Viagra

- Google’s search algorithm engine world dominance

Each of these things comes as a complete surprise to the vast majority of the population but is easy to rationalize with the benefit of hindsight.

These events are prospectively unpredictable yet become retrospectively predictable.

Our human nature, and recency bias in particular, can be our worst enemy when living in the “day-to-day” of a financial market.

It’s so easy to take what’s happened the last week or month and extrapolate that out over a much longer time frame.

When it comes to agricultural commodity markets, we all can take from the past but need to remember that each year is full of it’s own unique surprises.

Ag Markets are Full of Mini-Black Swans

Once again we almost always tend to minimize the probability of large price moves in grain markets.

Seasonal grain market moves often times comprise “smaller versions” of a Black Swan’s three traits.

- First, they feel like an outlier (“There’s no way the weather justifies a $.40 drop in the corn market this week!!”)

- Second, they carry high consequence to your farm

- Third, despite being outlier events we tend to create explanations for their occurrence after the fact, making them plausible/explainable/predictable (“I should’ve seen that rally coming, we were getting awfully dry! I won’t make the mistake of forward contracting again. That dumb ass Nick Horob and his blog posts about selling summer rallies!!”)

Let’s take a deeper dive. See below for an excerpt from a blog post I wrote last fall.

__________________

I was recently having a conversation with a farmer regarding his frustrations surrounding his grain marketing.

Specifically, he was extremely worked up over an accumulator-like corn contract he entered into on the rally this summer.

*Once again, even though I’m leaving this story anonymous I’ve asked for permission to share it. To me, nothing is more important than confidentiality.

He’s in an area that currently has a terrible corn basis. Earlier this summer, he made the decision that he was going to hold onto the last 20% of his corn and market it as new crop.

On the day he made this decision (mid-July), cash corn was trading for $3.00 in his area. He decided to do a March HTA at $4.15 March 2018. His area typically sees a $-.40 (or better) corn basis during the winter so that would equate to $3.75 cash price. That’s a heck of an ROI for six months of storage!

Well……that’s not what he did.

He got talked into a contract where he could get another $.10 if he were to agree to a “double up” at $4.50 and a “knock out” at $3.50. If March 2018 corn trades below $3.50, he gets kicked out of the contract on the remaining bushels (he gets locked into a small amount of the $4.25 net price every day that elapses).

He told me that 3 out of the last 5 years, he’s been able to get a $-.25 or a bit better basis so the thought of turning $3.00 cash corn into $4.00 lured him into the contract. Plus, who wouldn’t like an extra $.10 in today’s farm economy?!

There’s nothing wrong with contracts like this.

What’s wrong in these situations is that most of us tend to suffer from what’s called Recency Bias.

What is Recency Bias?

If you’ve been on this email list for awhile you’ve likely heard me talk about it before, but here is good definition of it.

“The recency bias is pretty simple. Because it’s easier, we’re inclined to use our recent experience as the baseline for what will happen in the future. In many situations, this bias works just fine, but when it comes to investing and money it can cause problems.

When we’re watching a bull market run along, it’s understandable that people forget about the cycles where it didn’t. As far as recent memory tells us, the market should keep going up, so we keep buying, and then it doesn’t. And unless we’ve prepared for that moment, we’re shocked and wondered how we missed the bubble.

When the market is down, we become convinced that it will never climb out so we cash out our portfolios and stick the money in a mattress. We know the market isn’t going back up because the recency bias tells us so. But then one day it does, and we’re left sitting on a really expensive mattress that’s earning nothing. (Source)”

The farmer above took the price action of the last week or two and extrapolated it out over the next few months. We’ve all done it!

What can we do to correct our Recency Bias?

Anytime we can remove our emotions from a decision making process, that’s a good thing in my opinion. Let’s approach this from a statistical point of view.

To correctly estimate the probability of price moves, we need an assumed forward-looking volatility of prices.

Without getting into too much detail, we can look at option prices to get an estimate of this forward-looking volatility. In option pricing models, volatility is the only unknown factor. Given that we know the market price of the option, we can calculate the volatility factor being used by the market (the implied volatility).

We are fortunate to have a valuable index to use in our calculations. The CBOT publishes an implied volatility index for corn, soybeans, and SRW wheat. Click here to see a chart of the CIV (corn implied volatility index).

“These contracts always stress me out!!”

The farmer above told me that he’s entered into these contracts and sold options a few time in the past. He also made a comment about how the market appears to “hunt” for his option strike prices with the intent to make his life as stressful as possible.

He was obviously being sarcastic and snickered at the thought…..but it can definitely seem like it!

To objectively look at situations like this we need to understand one key concept……The Probability of Touching.

It’s relatively straightforward to calculate the probability of an option expiring “in the money” or worthless but that’s not what we are going to focus on here.

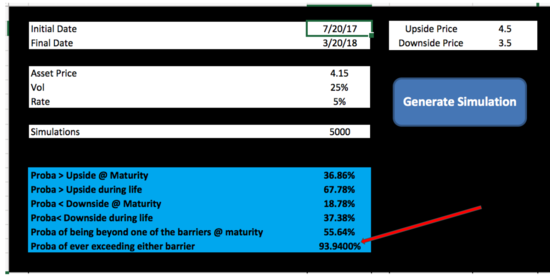

Given that this corn contract expiries if $3.50 March 2018 corn is “touched”, we need to understand the probability of this happening.

To accomplish this, we can use a technique called Monte Carlo simulation. In laymen’s terms, what a Monte Carlo simulation accomplishes is to quickly run a high number of random simulations to determine the probability of certain occurrences.

I recently had a statistician build me a Monte Carlo simulator in spreadsheet form. I’m going to make this available to anyone who’s ever signed up for our Business of Farming course.

Lets review the corn situation above. In mid-July, the implied volatility of corn was between 30-35%. For purposes of our simulation, I’m going to back the volatility down to 25%.

See below for the results of 5,000 random trials using our Monte Carlo simulator.

As you can see, in over 90% of the trials we exceed either the $4.50 or $3.50 strike prices of this corn contract.

We’ve yet to pierce either of these levels but the market has been uncomfortably close to the $3.50 level the last few weeks!

It’s no wonder this farmer joked that the market seemed to “hunt” for his short option strike prices!!

In summary, we almost always underestimate the probability of large price moves. There are countless instances…..the 2012 rally, the 2014 crash in the corn market, the 2016 soybean rally, the 2017 spring wheat rally…….and on and on!

__________________

So….how do we deal with these mini-black swans?

- Realize that hindsight is 20/20, and

- Respect the unpredictable nature of the future, and

- Focus on doing everything a little better with the goal of becoming the low cost producer (on a per unit basis)

In addition, (in my opinion) there’s a great comfort that comes from making decisions with your farm in mind instead of trying to predict the future.

I heard a quote a couple months back that really resonated with me.

“Business is like a game of soccer. You need goals. If there are no goals, you can’t win.”

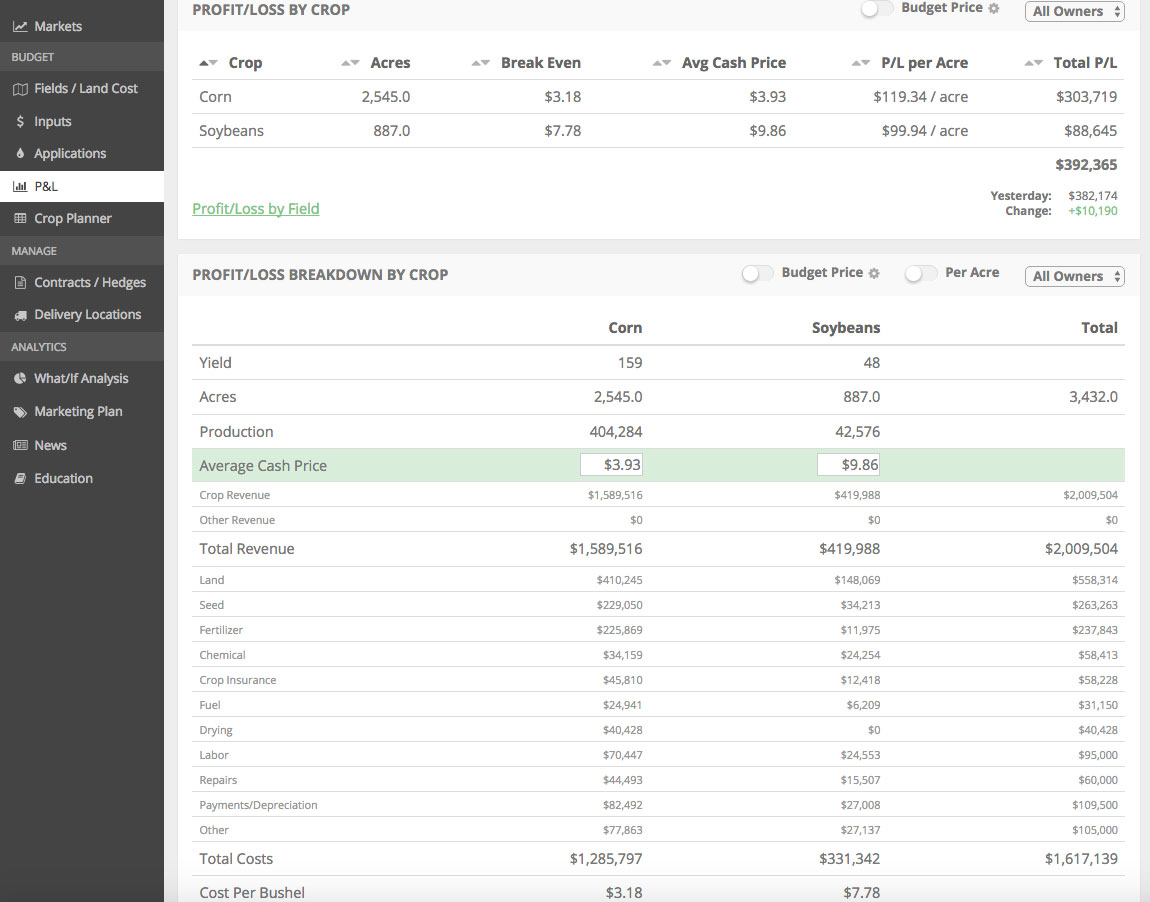

I relate that back to farm finances. Tracking your farm’s profitability won’t magically make your farm more profitable, but it will give you the confidence to make proactive decisions when facing these grain market and weather mini-Black Swans.

PS. Our sole goal is to help make this number tracking process easier for you. If you haven’t tried our software, click here to try a demo (or reactivate an old demo account you set up).

Nick Horob

Passionate about farm finances, software, and assets that produce cash flow (oil wells/farmland/rentals). U of MN grad.

Related Posts

Grain Marketing can be an Emotional Roller Coaster

Grain marketing is hard! Volatile commodity markets lead to frustration, greed, and indecision. Today's farmer needs to work hard to find a risk management system that allows them to make less emotional, and more profitable, grain marketing decisions.

Read More »