For now, this is the final post in our series on how cognitive biases cans lead rational people to making irrational decisions.

As a farmer, you make 100’s, if not 1,000’s, of decisions during any growing season.

From what you’ll plant, to when you choose to market your crop, and everything in between.

Research suggests that we aren’t as rational of thinkers as we think we are.

That can be especially true in an industry such as farming where so many factors influencing your financial outcome (weather, markets, etc) are outside of your control.

This uncertainty can lead to irrational decision-making. Much of this irrationality can be attributed to the effects of cognitive biases.

Click here to read Part 1 in this blog post series.

Click here to read Part 2 in this blog post series.

Click here to read Part 3 in this blog post series.

With that, here’s Part 4 in our series on how biases can negatively impact your farm management decisions.

Bias 10 - The Endowment Effect

One hidden job of farmers is that of being an asset manager.

Farmers manage relatively large amounts of intermediate-term and long-term assets. Furthermore, these assets tend to follow the roller coaster cyclicality of the overall commodity markets.

Managing that volatility isn’t easy.

Today’s bias is an interesting one that completely fits some decisions I’ve seen on the farm and runs counter to a few farm asset allocation decisions.

In behavioral economics, the endowment effect describes the behavior of people tendency to ascribe more value to things simply because they own them.

In one example of the endowment effect at work (source), participants first given a 400-gram Swiss chocolate bar were generally unwilling to trade it for a coffee mug, whereas participants first given the coffee mug were generally unwilling to trade it for the chocolate bar. See below for the study’s specific results.

- Initial choice between a chocolate bar and coffee mug: 56% chose the mug & 44% chose the chocolate bar

- When first given a mug and then offered a chocolate bar: 89% kept the mug & 11% chose the chocolate bar

- When first given chocolate and then offered the mug: 10% chose the mug & 90% chose the chocolate bar

Wow

If you’re really a behavioral finance/economics nerd like myself, here’s a link to an interesting study that involves the endowment effect at work with NCAA tournament basketball tickets. I warn you, it’s great but definitely dense.

There seems to be some debate on this bias as it doesn’t appear to apply to all goods/markets. For example, it seems to be more of an issue with goods that wouldn’t normally be bought and sold on the open market.

I see this on farms. While I’ve definitely come across a few situations where farms “sat” on aging farm equipment to the point where it becomes detrimental to their efficiency, most understand it’s a market that fluctuates.

I spent some time last night thinking about how this applies to the farmland market….

Owners of farmland definitely have some extra motivation to hold on to it in a declining market. But it’s almost as if farmland market participants sometimes suffer from a preemptive endowment effect. They feel the “attraction” of owning the land before they actually do. I need to dig into this one a little more…..

I should note that I’m not a person who perpetually says “farmland doesn’t pay”. Farmland is a great long-term wealth builder. But to build wealth in the long-term you need to pay for it in the short-term.

All-in-all, the endowment effect isn’t as prevalent as some of these biases due to the liquid nature of most farm-related assets.

Keep aware of it and try to fight the effects of it if you’re ever faced with a less-the-ideal situation where good business sense tells you to turn some intermediate or long-term assets into cash.

On to the next bias!

Bias 11 - The Ostrich Effect

This bias hits home for those participating in an industry exposed to cyclicality and volatility.

Does that sound familiar?

Farming is notoriously cyclical and volatile.

Sometimes during periods of declining financial performance, we (as humans) have the tendency to ignore that data.

The name of this bias/behavior comes from the common, and false, myth that ostriches bury their heads in the sand to avoid danger.

The term ostrich effect was originally coined by researchers Dan Galai and Orly Sade in 2006 (source). They observed an anomaly in the relative value of a liquid and comparable illiquid asset. During a prolonged period of time, Government T-bills provided a higher Yield to Maturity than an equally risky illiquid asset (bank deposits). They couldn’t attribute it to taxes, risk, or transaction costs.

Specifically, they came to their conclusion by finding that the difference between the return on the liquid asset relative to the illiquid asset is higher in periods of greater uncertainty.

They used the term Ostrich Effect, to describe investor behavior since ostriches are believed to treat apparently risky situations by pretending they do not exist.

A different study conducted in 2009 (source) applied a broader definition to the Ostrich effect. This group defined it as “avoiding to expose oneself to [financial] information that one fear may cause psychological discomfort”. The found that people in Scandinavia looked up the value of their investments 50% to 80% less often during bad markets.

The examples of this bias at work in farm finance and risk management decisions are a bit more obvious with this one vs. previous biases.

Warning….I’m going to “speak out of both sides of my mouth”.

I think farmers should utilize the Ostrich effect in certain situations on try hard to fight it on others.

When is the Ostrich effect beneficial?

A quick story….

I was talking to a good friend who farms this fall. At the time, he made a comment something similar to “So and so market analyst told me that soybeans have price resistance at $9.67”.

At the time, soybeans were trading at $9.65ish. He was watching the soybean his cell phone like some sort of a drug addict.

Fixating on these penny by penny moves is counter-productive. Odds were highly likely soybeans are going to have more than a $2 range over the next year.

Sometimes, a person just needs to be aware of price volatility instead of checking prices 10+ times per day.

Focus your time on things you have more control over…..agronomic split tests, balance sheet optimization, landlord communication, etc.

Make a sale/hedge and move on to other activities. Watching financial markets closely won’t improve your ability to predict them (in my opinion).

That obviously doesn’t mean you should ignore them entirely……along with other aspects of your farm’s finances.

When is the Ostrich effect detrimental?

If you’ve been following our blog for awhile, you probably read the blog post we sent out that was written by a lender who had advice on successful farm/bank relations.

If not, the blog post is located here.

One of the main points of this article was that farmers need to know their finances. Here’s a quote from the article:

“It is absolutely critical the borrower knows their finances, in good times and bad. Future plans have to be based upon accurate historical, up-to-date information that appears reasonable. If an operation is reliant upon a third party or the lender to prepare their financials and then tell them what they mean, they tend not to understand the numbers. Management decisions are not made proactively based upon the financials under those circumstances. A lender is going to have a difficult time accepting a restructure package that includes projections that have a wide deviation from historical numbers.”

Knowing your numbers throughout the year, not just during winter meetings, allows you to proactively attack weaknesses. “Hiding and avoiding” is simply a recipe for disaster.

Here’s another great quote from that post:

“A huge mistake of the 80’s was to blindly keep operating and hoping for a change versus making a serious assessment of where the operation has been headed and realistically evaluating if it can change directions. Too many operations kept burning equity versus simply quitting or making major changes. The more time passes and losses accumulate, the more equity is consumed and options evaporate.”

All-in-all, the key lesson regarding this bias is that there’s no need to fixate on commodity prices on an hourly basis but you need to have your thumb on the pulse of your farm’s P&L.

Nothing you or I do can influence future weather or commodity prices but you can strive to make small improvements that lead to large cumulative gains in your farm’s equity.

That’s all for the ostrich effect.

Bias 12 - Anchoring Bias

This bias is one of my favorites. I find myself saying that a lot! Regardless, it’s good and highly relevant.

It’s closely related to bias 5, the Contrast Effect. I’ve included the email from bias #5 in its entirety below my signature.

Today’s bias can pop up in our lives in many situations.

Anchoring is a cognitive bias that describes humans’ tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information offered (the “anchor”) when making decisions.

Anchoring can be quite dangerous….

Anchoring commonly rears its head in decisions or situations involving pricing.

I’m sure many of you are familiar with the show Pawn Stars. Have you ever noticed that the first offer they give to a seller is often shockingly low?

They do this to then anchor the seller to that price.

Let’s assume that I go to the Pawn Shop and try to sell them our Excel for Farmers course for $100 (a damn steal in my opinion!!). I tell myself I won’t accept any less than $75.

I go in and plead my case about how this is the best Excel for Farmers course IN THE WORLD.

They respond with, “Nick, I know nothing about your Excel for Farmers course or farming for that matter.”

I ramble on and on about how great it is and the buyer throws out, “Nick I’m going to take a stab and offer you $10 for a ticket to this course.”

I respond with, “#$#!&, I need at least $60 to pay for the support that goes along with it.”

They respond, “Nick, once again I know nothing about farming and this course so I’ll offer $12 for a ticket”

I again plead my case!

They respond again, “You know what Nick I don’t think I can do it………………….but, I’m going to take a risk here and buy it for $25”

I quickly realize that he went from $10 to $12 and then more than doubled it to $25, so I blurt out “SOLD!”

I leave the store and realize, “Huh, I just sold that course for 1/3 of my lowest acceptable price. How did that happen?!”

He had me anchored to the $10 price. $25 is 150% more than $10.

I’m obviously being a sarcastic here but I’ve seen this play out a couple times first hand in mediation sessions. I’ve seen skilled litigators use anchoring to really bend the will of stubborn people in negotiations.

I realize that not everyone is going to be involved in high stakes mediation, so let’s focus on a more relevant example.

Price Anchoring in Grain Marketing

Let’s assume you have a $5 wheat breakeven at an APH yield heading into a crop year.

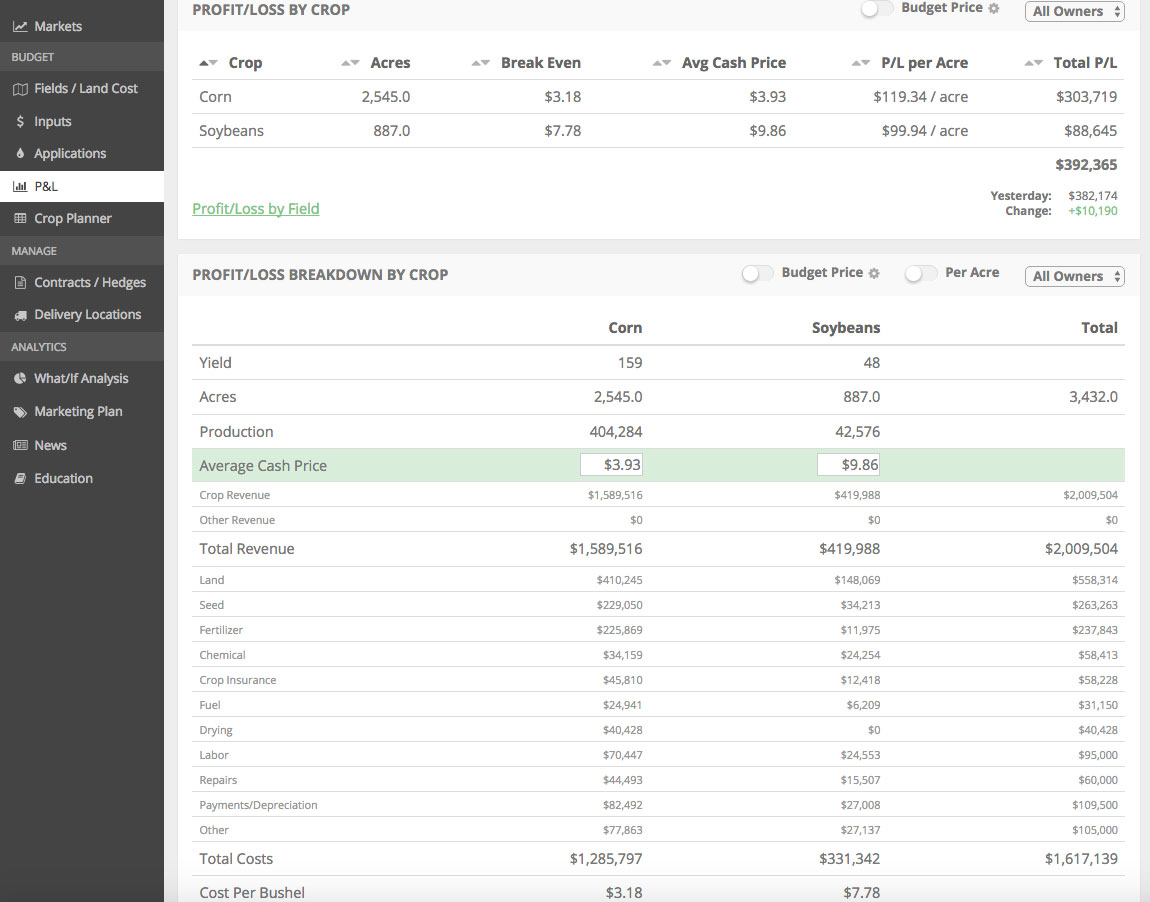

Thankfully, you sell a summer rally and are blessed with an above average crop. After adjusting your Harvest Profit P&L (shameless plug, I know!) you determine that your breakeven on your unsold bushels is now $3.97.

You call your local grain merchandiser and give him/her some grief about their crappy basis but find out the cash price is still a respectable $4.70.

You immediately think to yourself, “when we get back to $5.00, I’ll make a sale”.

Why $5.00? It’s your price anchor. It doesn’t really mean anything to you at this point.

I could tell countless stories about this (including some from my own mistakes) but it’s relatively straight-forward. Don’t anchor to something meaningless.

Once again, see this blog post that discusses the contrast effect. It’s the nasty cousin of the anchoring bias.

On to the final bias in our series!

Bias 13 - Recency bias

I see this bias at work more than any other.

While it comes up in many situations, it’s very prevalent in human decisions regarding financial markets.

Furthermore, if you’ve been following our blog or my emails you likely know how important I feel it is for us to realize the effects of it.

Recency bias refers to the human tendency to overemphasize more recent data.

Let’s look at some examples.

I know a guy who runs a precious metals retail store. After a sharp decline in the price of gold, I asked him about that week’s sales. He told me it was one his worst weeks of sales in years.

Every investor has heard the philosophy of “buy low, sell high”, right?!

Similarly, as I’ve got to know a number of grain merchandisers over the years I’ve asked them similar questions. On numerous occasions, I’ve asked: “Nice to see this rally, did you buy a lot of grain this week?”

Their answer is highly dependent on the timing of the rally.

If it marks a change in direction (eg. a rally after a prolonged downtrend), they buy a lot of grain. If it’s a continued rally, the selling tends to dry up.

At work in each of these examples is a phenomenon known as recency bias, which is our tendency to believe that an event is more likely to happen again because it occurred in the recent past. The inverse is also true, the longer it’s been since something took place, the less likely we are to believe it will happen in the near future.

In the reversal of a downtrend, it’s easy to focus on the recent bear market. “I better sell!”

In a continuation of a rally, it’s easy to focus on the recent uptrend. “My last sale sure looks cheap, I’m not making that decision again!”

What can you do about it?

I’m going to focus on grain marketing but much of this thought process can be applied to any other decision where they recency bias can handcuff you.

- Realize that price prediction is nearly impossible, specifically the timing of price moves. (eg. who predicted oil would drop from $100 to $30? How many predicted that oil was doomed after we already had fallen $50+? This happens over and over in financial markets.)

- Use the seasonal tendencies to your advantage. Premium prices tend to occur during periods of where the crop can put in peril. This most often occurs from April-July. Making panic sales below your cost of production during the winter is rarely the right thing to do. Put your self in a position where you don’t need to make sizable marketing moves during these seasonally weak times of the year.

- Know your numbers. The market doesn’t care about your specific cost of production, obviously! But knowing your numbers will allow you to make confident risk management decisions in the face of always-changing commodity prices.

- Make a decision and don’t look back. Don’t let past decisions handcuff you from taking advantage of profitable marketing opportunities. What’s done is done!

- Don’t judge your decision based solely vs. the market. You need to judge your decision based on how it impacts your long-term farm business goals.

- Don’t underestimate the benefit of reducing risk. Grain marketing tends to be viewed as a way to maximize your revenue, which isn’t wrong. But, too often, it’s easy to forget about the benefit of reduced risk. A profitable sale or hedge may reduce your worst-case loss from $100/acre to $50/acre regardless of if a “better” pricing opportunity occurs in the future. This isn’t easy and it likely never will be but being prepared and recognizing that the bias exists costs very little.

Quit letting yesterday (or last week, month, year) be the primary factor in determining what you do tomorrow with your farm/risk management decisions.

Finally, hindsight is crystal clear and the future is quite foggy. That will never change.

That wraps up our initial series on how cognitive biases can screw up farm management decisions.

I’m a firm believer that studying biases can have as high of an ROI on your time as nearly anything.

Identify these cognitive biases in your life and business and side step them when they rear their ugly head!

If you find value in content like this, sign up for our free e-mail newsletter below.

Nick Horob

Passionate about farm finances, software, and assets that produce cash flow (oil wells/farmland/rentals). U of MN grad.

Related Posts

13 Biases That Screw Up Farm Management Decisions - Part 1

In this blog post, we are jumping into the world of cognitive biases. In particular, we are focusing on how our biases can screw up management decisions on the farm.

Read More »13 Biases That Screw Up Farm Management Decisions - Part 2

In this blog post, we are continuing to investigate cognitive biases. In particular, we are focusing on how our biases can screw up management decisions on the farm.

Read More »13 Biases That Screw Up Farm Management Decisions - Part 3

In this blog post, we are continuing to investigate cognitive biases and how they impact farm management decisions. Biases play a key, and often hidden, role in many of the decisions business owners make. In a business with as many decisions as farming, you need to be aware of their potential negative impact on your farm.

Read More »