Given the current state of the farm economy, there are going to be some tough discussions and decisions this winter regarding cash rent contracts.

Many of you may be trying to renegotiate the amount of cash rent you’re paying or countering a proposal from a landlord. To help you with that process, I want to give you a framework for negotiating cash rent. This negotiation framework comes from the real estate investing and private equity industries, used when negotiating large multi-million dollar transactions.

I will also touch on the decision-making process regarding what to do when your rent negotiations don’t yield positive results. I’ll try to provide a decision framework to help you answer, “Should I keep farming this high-rent piece of farmland?”.

First, while many cash rent negotiations occur verbally I recommend also putting your thoughts into a letter. Here is how I would recommend structuring a letter.

- Appreciative Introduction: Use the opening paragraph of your letter should as an opportunity to show that you appreciate the opportunity to farm their land.

- Include Farm Details: During the opening of the letter include some specific details on their farm. You could mention their farm’s actual yield for this year, discuss a recently completed farm improvement project, ideas for them to further improve their farmland, etc. You want to give them a piece of information on their farm that they don’t already know about. Show them this isn’t a standard form letter and that you are writing it to them, not just a group of landlords.

- Get Straight to the Point: After an appreciative, personalized introduction get straight to the point and mention the goal of your letter. Simply state the objective and quickly follow-up with facts that support your objective.

- Present the Facts: Presenting a numbers-based analysis will support your position. This analysis can include, but is not limited to, 1) actual P&L for their farms, 2) actual input cost data, and 3) university cost of production budgets. It’s important to note that actual input cost data or university-published budgets will carry more weight than something you create. See below for more information on university budgets.

- Offer Upside: The majority of landlords aren’t open to flex rent structures. Regardless of this, it’s your job to present this option to them. State that you’d like nothing more than to be able to pay them (insert high rent rate here) but the current market doesn’t allow for that. Show them a structure where they’ll be able to achieve MORE than their rent objective if we have a material commodity price rally.

To assist in supporting your communications with facts, see below for my list of links to cost of production budgets from universities around the country.

- Iowa State University Costs & Returns

- University of Illinois Production Costs

- University of Minnesota Crop Budgets

- University of Minnesota Farm Financial Database (great resource!)

- North Dakota State University Crop Budgets

- Ohio State Farm Management Enterprise Budgets

- Purdue Crop Costs Guide

- Michigan State Cost of Production Budgets

- South Dakota State University Crop Budgets (link to spreadsheet)

- University of Nebraska Crop Budgets

- Kansas State Projected Budgets

- Oklahoma State Enterprise Budgets

- Texas A&M Crop and Livestock Budgets

- University of Wisconsin Field Crop Enterprise Budgets

- Montana State Cost of Production Calculator

- Alabama Enterprise Budgets

- University of Arkansas Enterprise Farm Budgets

- Mississippi State Ag Economics Budgets

- University of Missouri Crop and Livestock Budgets

- University of Tennessee Crop and Livestock Budgets

What to do if your rent negotiations don’t yield positive results?

Here’s a decision framework for deciding whether or not to continue farming a high-rent piece of ground. The goal is to be objective, not emotional.

This first thing you need to do is have your 2017 crop budgets fine tuned. Two data points you’ll need to focus on are:

- What is your overall cost of production at your current rent?

- How would letting this farm go affect your overhead per acre?

Lets work through an example. Note that theses are all assumptions and the point is not to focus on the individual numbers but to focus on the the thought process.

Let’s assume a producer raises corn and soybeans in a 50/50 rotation on 2,500 acres. Their average corn yield is 175 bushels/acre and their average soybean yield is 50 bushels/acre. They have a 500 acre rent contract coming up for renewal and the landlord is “set” on receiving $350 per acre. After a much back and forth, the landlord won’t move from their $350/acre ask.

To begin, here are the current land costs for this producer.

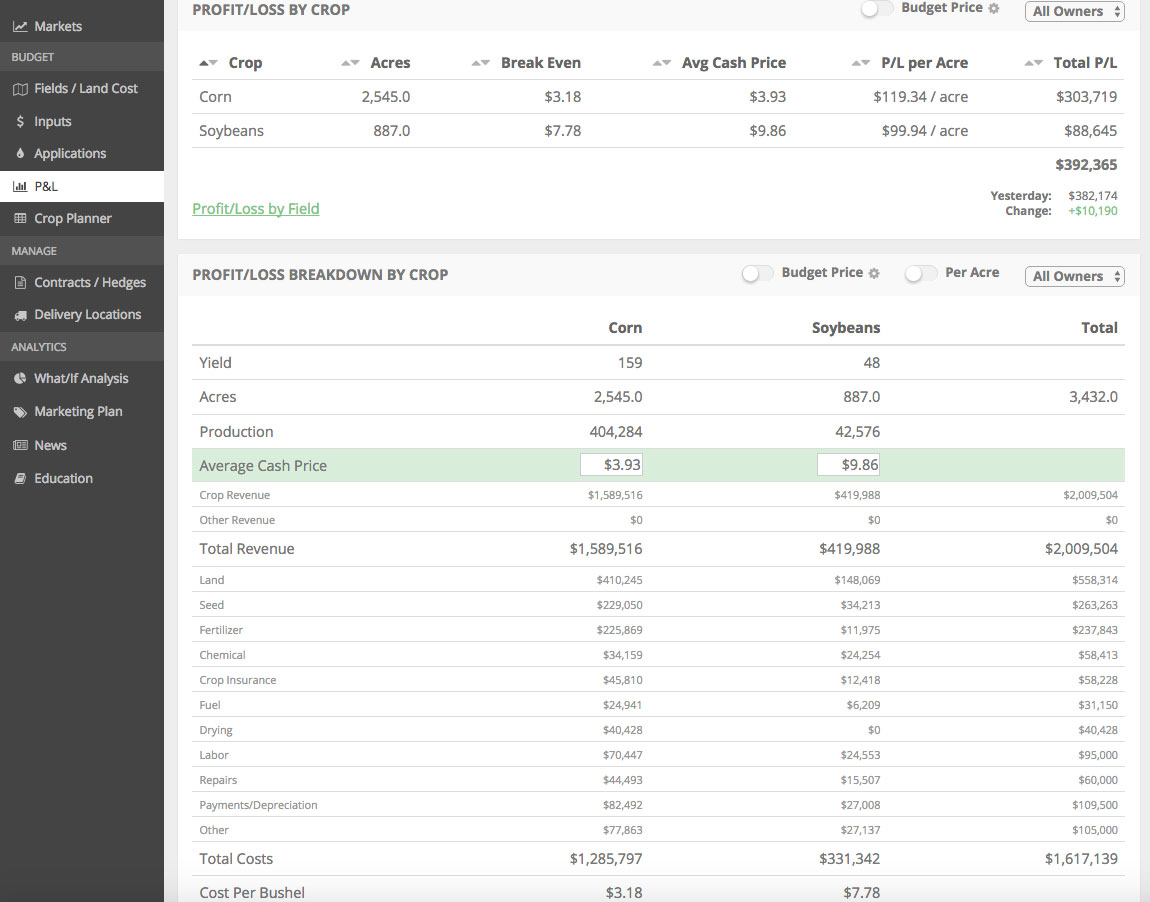

We know $350 rent is too much in today’s environment but let’s take a look at this farm’s cost of production using that level of rent. We are going to analyze the $350 rent on its own, not the farm’s average total land cost.

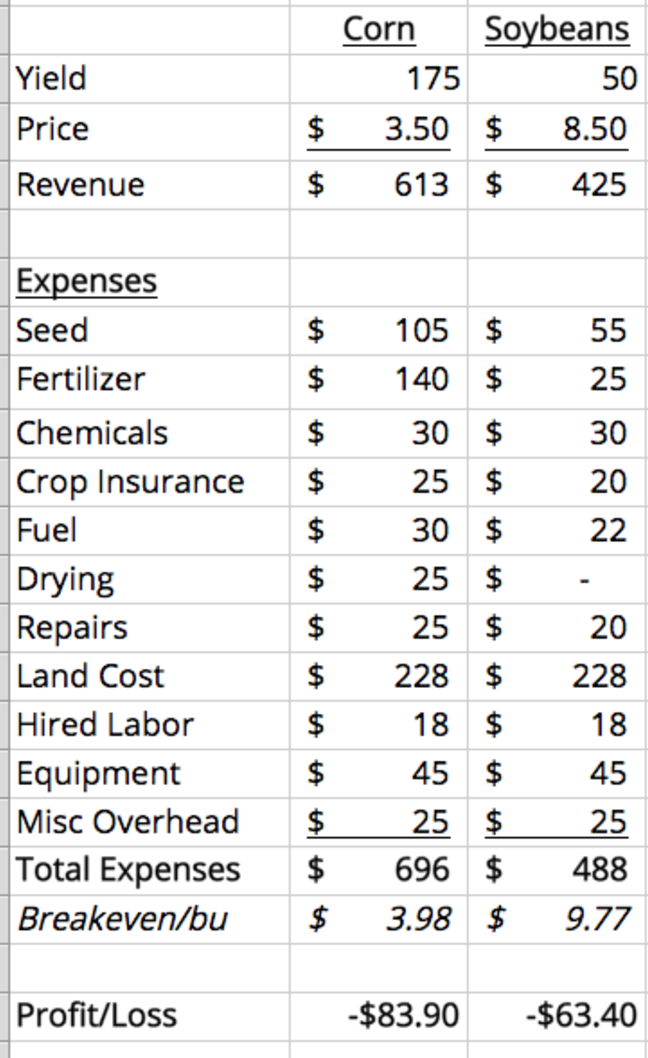

There isn’t much that needs to be said about the above table. $350 doesn’t work in today’s price environment. Let’s take a look at the farm’s total projected P&L to see if their other rented and owned land can “buy time” and subsidize the $350 cash rent.

We are still looking at an average loss of approximately $75/acre. Ouch! Right now we are fairly certain that the $350 cash rent farmland is too expensive for this farm to continue farming. If we let the 500 acre farm go we will have to spread our overhead out across less acres, essentially increasing our per acre cost of production.

Farm Overhead Analysis

I’ve greatly simplified this overhead analysis to include only three line items but the thought process is the same as the real world. We want to analyze expenses that don’t change on a per acre basis. Let’s analyze our per acre overhead at 2,500 acres and 2,000 acres.

If we let the 500 acres go, our overhead will increase $22/acre.

Common sense tells me that a $22 increase in this farm’s overhead isn’t enough of an increase to justify paying the $350 cash rent. Let’s analyze our overall cost of production if we decide to quit farming the 500 acres up for renewal.

Conclusion

The results are a bit surprising to me. Letting go of a farm that has a rent $120 higher than the average rent on our other contracts would only save us $23/acre (after the $22/acre increase in our overhead). Dropping this farm would be a “no brainer” if we could also drop some overhead. Having our per acre overhead increase $22 per acre materially reduces the cost-effectiveness of this farm letting go of the high rent farmland.

With that said, saving $23/acre amounts to $46,000 for a 2,000 acre operation. That is real money, especially if you multiple that amount over a 2-4 year time period.

There are obviously additional factors to consider in this analysis. The quality of the farmland and its yield potential is a primary question.

All-in-all, numbers don’t lie. Doing objective, numbers-based analysis will help a farming operation make the best decisions possible in these uncertain times.

Our Mission to Help Farmers With This Type of Analysis

There are a lot of awesome tools for producers on the agronomic side of the farm but we feel there is a lack of easy-to-use, intuitive farm business tools in the market place.

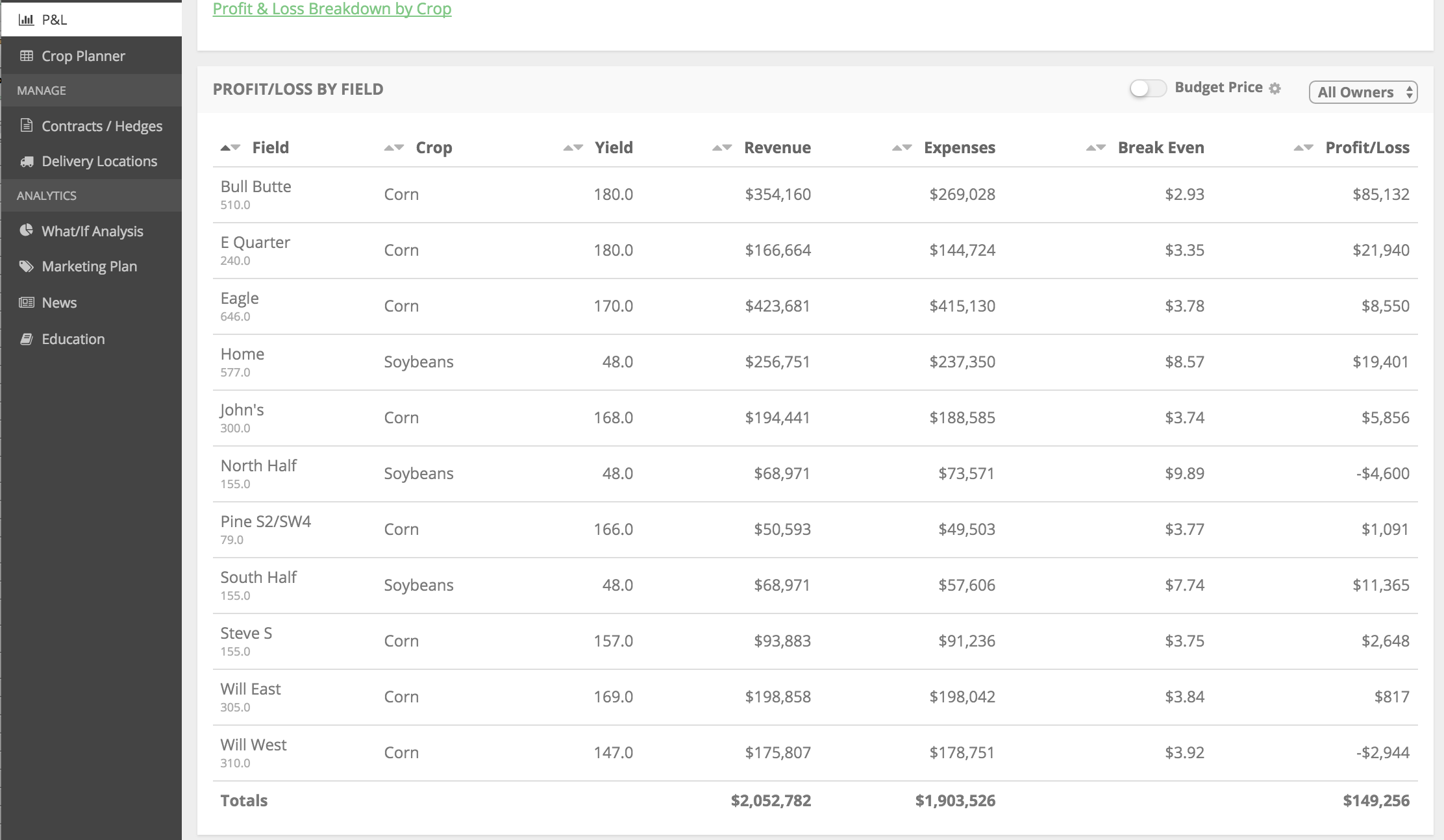

To help producers with this type of analysis, we are building suite of farm finance tools. This will include a field-by-field farm financial package where producers can build field-by-field budgets and analyze historical field financial performance.

With the a couple clicks you’ll be able to quickly see what fields are making you (and losing you) the most money.

Here’s our field-by-field profit/loss analysis software tool.

We’re decicated to helping farmers make sound farm financial decisions. We’ve recently released our suite of farm business software tools. If you’re interested in learning more about our software or are interested in receiving articles similar to this, please sign up for our access to our free demo account below.. We’re not a fit for everyone but we’d love to work with your operation.

Nick Horob

Passionate about farm finances, software, and assets that produce cash flow (oil wells/farmland/rentals). U of MN grad.

Related Posts

Farming Bigger Isn't Always Better

Farming bigger isn't always better. Learn from the success of a mid-size operator with a $10 million net worth.

Read More »