Based on conversations we’ve had with many growers, the pace of farmland changing hands has picked up over the 12-18 months.

Given that, we wanted to share with you some considerations you should make when faced with these opportunities. We will also walk through the process for how to thoroughly evaluate the numbers behind these decisions.

This first thing we need to understand when making these decisions is that it is a mix of art and science.

- The science is the number-crunching

- The art deals with the fact that these decisions can be emotional and your biases can trip you up

Let’s first focus on the art of thinking about new land.

1 - “If you’re not growing, you’re dying”?

While it’s true that farms are consolidating and growing in size, I think many businesses selling to farmers use this as a scare tactic.

The vast majority of the most successful farms I’ve worked with have had at least one period of downsizing in the last 7-8 years. When you track your farm’s profitability on a field-by-field basis over multiple years, it becomes easy to see when certain farms act as an anchor to your profitability.

Just like adding farms to your operation can be a powerful way to leverage your labor and fixed expenses, sometimes letting land and it’s associated overhead go is the way to increase your bottom line.

Long story short, don’t grow your operation just for growth’s sake. Do it because it makes sense for your farm!

2 - “I can do a better job of farming it”?

We as humans tend to suffer from overconfidence bias. This bias can lead us to think that we can do a better job with a farm than a previous tenant or owner.

Overconfidence is one of the largest and most impactful of the many biases to which human judgment is vulnerable.

Here are a few examples of overconfidence bias at work.

- 93 percent of drivers in the US claim to be better than the median, (1) which is obviously statistically impossible

- Another way in which people can indicate their confidence about something is by providing a 90 percent confidence interval around some estimate; when they do so, the truth often falls inside their confidence intervals less than 50 percent of the time, (2) suggesting they did not deserve to be 90 percent confident of their accuracy

- Daniel Kahneman, the author of the best-selling book Thinking Fast and Slow, called overconfidence “the most significant of the cognitive biases.” Among many other things, overconfidence has been blamed for the sinking of the Titanic, the nuclear accident at Chernobyl, the loss of Space Shuttles Challenger and Columbia, the subprime mortgage crisis of 2008 and the great recession that followed it, and the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. (3)

Simply be aware of overconfidence bias when you are evaluating new farm rent opportunities.

3 - “If it doesn’t work, I’ll just let it go!”

When evaluating a new rent opportunity, it can be easy to assume that if it doesn’t work as planned…..you’ll simply let another tenant take over at the end of your contract.

I’ve seen a number of instances where a grower picks up a new piece of ground with a mental agreement with themselves that if it doesn’t work, they will let it go. It’s awfully easy for another bias to rear its ugly head and prevent you from following through with this plan.

The bias is choice-supportive bias. Choice-supportive bias is the tendency for a decision-maker to defend their own decision or to later rate it better than it was simply because they made it. This can easily lead to you sticking with unprofitable decisions longer than the financials of the decision warrant.

It’s never easy to admit that we made a poor decision.

Now we are going to jump into the science of analyzing a new farm rent/purchase situation.

4 - Build a field-by-field financial model

While you don’t have to do this when simply making an up-front farm decision, you’ll want to have this model in place to evaluate the decision down the road.

As you likely know, the main benefit of adding land is spreading your overhead out across more acres.

The “bare bones” method of evaluating a new opportunity simply involve making realistic estimates of the following.

- Revenue

- Variable expenses

- New overhead required (eg. equipment payments)

You’ll want to be careful to consider how your storage will play into this. Having on-farm storage and drying capacity to absorb incremental production will show a meaningfully different outcome than having to deliver all of the production to market at harvest.

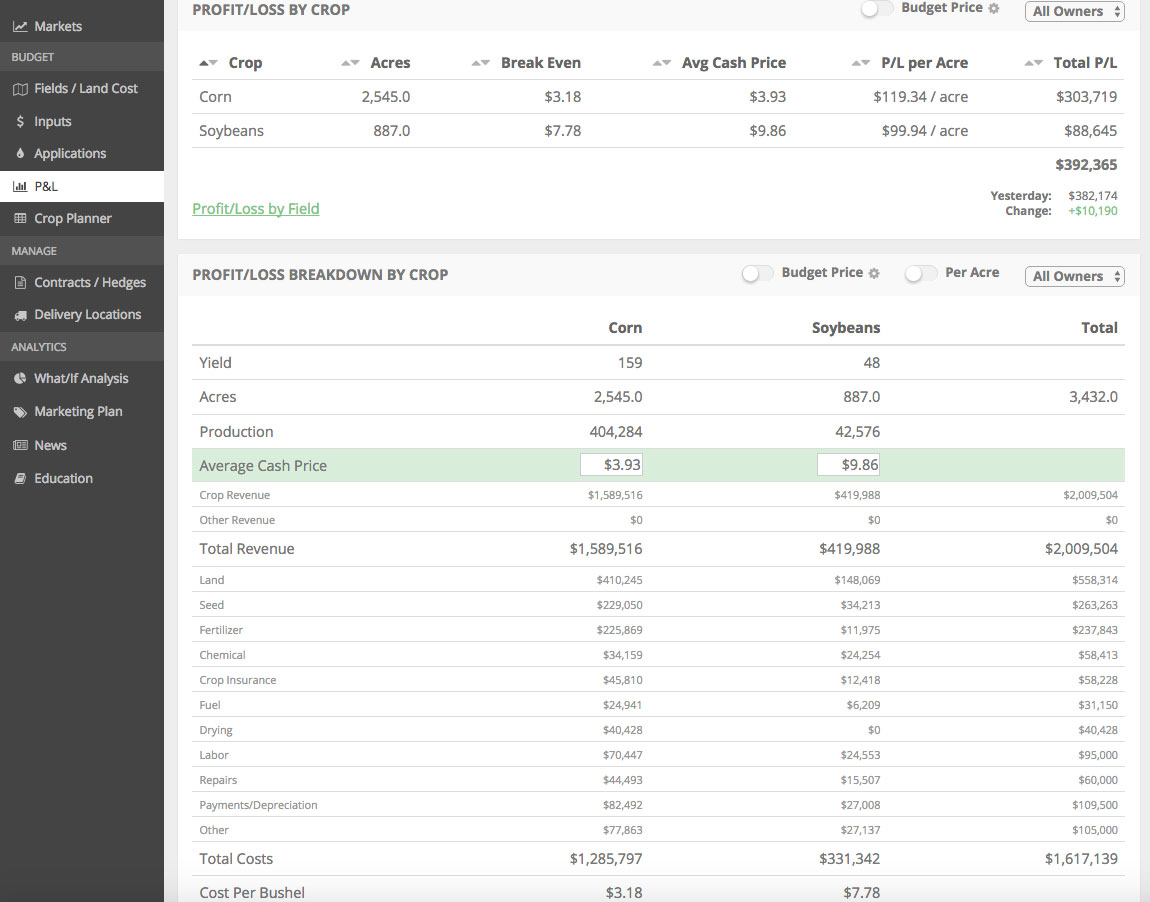

Once again, Harvest Profit allows you to quickly “archive” your fields to view a before-and-after view of your bottom line in about 5 seconds. In the picture below, I have a field excluded from my P&L. If I click the “unarchive” button, the field’s revenue, variable expenses, and overhead will all be included in my financials.

The enterprise-level math isn’t rocket science but I still firmly believe that a per field financial model is necessary to truly evaluate your farm like the manufacturing business it is.

99% of successful manufacturing businesses evaluate their profitability by facility, why should a farm be any different?

5 - Be Aware of “Cost Creep”

Many, maybe even most, rent opportunities will make sense if you aren’t required to add overhead to farm the ground.

But I need to warn you of a phenomenon I call “Cost Creep”. Even if you don’t need to add any equipment or labor to take on a new opportunity, smaller increases in cost line items can creep into your financials.

For example, maybe you find yourself not being able to spray your crop in as timely a fashion as you’re used to. So you hire someone to come in a custom spray a couple of fields. The custom rate (plus potentially higher chemical prices) could easily cost you an extra $5-10+/acre vs. doing it yourself.

There are 100’s of little things that can lead to Cost Creep on your farm.

if you want to see real-world examples of this from other industries, go to Yahoo Finance and look at the financial statement of any growing business. Find their Selling, General and Administrative Expenses line item and it will be growing right along with revenue in the vast majority of companies.

If/when they see a decline in revenue, they can see very fast profit margin compression. You, as a farmer, know what I’m talking about here!

Be aware of Cost Creep when evaluating new opportunities.

6 - Analyze Working Capital Impact

As I mentioned above, many rental opportunities will look good from an income statement point of view due to the impact of spreading out your overhead (it’s getting repetitive, I know!).

It’s not as easy as that though! Obviously….

In farming, the two main variables that impact your bottom line our outside of your control. The weather and the grain markets. You can and should use grain marketing/hedging to manage your price risk, but that’s outside of the point of this post.

Due to weather and grain market volatility, it’s inevitable that you are going to experience a loss on your farm (once again, this is common sense).

Working capital is a form self-insurance that protects you from having a loss put you out of business.

In case you don’t already know, working capital is current assets minus current liabilities.

Your farm’s working capital is essentially what’s left over (in assets) after you pay off all of your short-term liabilities, including your operating note.

If your farm loses its ability to repay it’s operating note in fall, your lender will likely require you to refinance (or sell) your intermediate or long-term assets to generate enough liquidity to pay off your operating note.

Let’s look at a scenario with the following variables. (I don’t like to focus on just corn and soybeans given that our customers grow many different crops, but we need to pick some crops to make the math as relevant as possible)

- Corn acres: 500

- Corn average yield: 175 bu

- Corn fully-burdened cost of production: $600

- Corn cost/bu of average yield: $3.43/bu

- Soybean acres: 500

- Soybean average yield: 45 bu

- Soybean fully-burdened cost of production: $400

- Soybean cost/bu of average yield: $8.89/bu

This farm has $150,000 in working capital or 30% of the total expenses of $500,000.

Let’s assume that this farm has an opportunity to pick up 700 acres of land from a retiring neighbor at a reasonable land cost. What an awesome opportunity!

Let’s look at the revised variables for this farm (note that we are making some assumptions here that we won’t fully dive into).

- Corn acres: 850

- Corn average yield: 175 bu

- Corn fully-burdened cost of production: $575

- Corn cost/bu of average yield: $3.29/bu

- Soybean acres: 850

- Soybean average yield: 45 bu

- Soybean fully-burdened cost of production: $380

- Soybean cost/bu of average yield: $8.44/bu

The total expenses of this farm now increase to $811,750. Their $150,000 of working capital is now 18.5% of expenses vs. 30% before the acreage increase.

The next step would be to stress-test the downside of the revenue after the expansion with a big focus on the insurability of the added acres (from both a crop insurance and grain marketing standpoint).

If you have good insurance coverage, the lower overall expenses and breakevens associated with the land addition make this an attractive deal (in most scenarios).

If the market is well below cost of production and crop insurance guarantees are as well, then a person might think twice about the hit they’d be taking to their working capital.

At the end of the day, you want to bulletproof your farm from the 1-in-10 type of poor year and working capital is a big piece of your farm’s bulletproof vest!

7 - Where are we at in a typical commodity S&D cycle?

Returns in farming tend to be cyclical in nature.

We experience a few years of good returns followed by a few years of negative returns. That is the inherent nature of agriculture as it is a competitive industry.

High prices cure high prices and low prices cure low prices.

When reviewing new rent opportunities, you need to review where were are at in this cycle.

I know this seems like common sense but humans tend to suffer from recency bias. It’s easy for us to take the events of the last month or two and extrapolate them over multiple years.

A simple thing to do is to review the general sentiment in the ag industry. If we are in the midst of the “good times”, be cautious when presented with opportunities to rent new farms.

8 - Are there ways to manage the downside?

So I just got done saying that you should be especially cautious when presented with opportunities to pick up new land during periods of higher prices/profitability. I’m going to go against that sentiment right now.

If there are opportunities to greatly reduce your risk via grain marketing and/or crop insurance, then you’d be foolish to not consider growth opportunities during cyclical highs.

In 2011, I met a younger farmer who had just doubled his farm size via a couple of two-year rent contracts that were high when compared to the average rent in his area over the last 5-10 years. When talking to him about the thought process behind taking on these rents, this farmer had a very logical approach.

Here are the factors that went into his decision.

- He had relatively high APHs

- The projected insurance price for 2011 corn, and he was going to be heavy corn, was trending towards a $6.00 projected price. It ended up at $6.01.

- He forward contracted 50% of his expected ‘11 yield and 25% of his expected ‘12 yield when the new contracts were signed.

He told me that he had done some analysis at the time where he fully locked in a profit for 2011. I’ve recreated a profit matrix using figures that should be very close to what he experienced then ($4.15 breakeven, 50% sold at $5.25).

What sounded like a “high” cash rent, using historical standards, offered the rare case where the chance for a loss could be nearly eliminated.

The interesting thing about this story is that the “coffee shop” thought this grower was surely to “loose his butt” on this deal. But if you fast forward a few years, many of these same people were paying this same rent but futures prices had fallen $1.00-2.00/bushel across most crops.

This farmer ended up letting one of the farms go as the landlord wanted another rent increase even after prices had dropped quite dramatically but he’s been able to add additional farms to his operation over the last 3-4 years. He’s now getting to the point where he’s stretching his one line of equipment quite thin but that’s a conversation for another day!

All-in-all, if you can eliminate much of the downside risk of an acquisition then you owe it to yourself to ignore the potential rumors and make it happen!

As Warren Buffett said, “Opportunities come infrequently. When it rains gold, put out the bucket, not the thimble!”

Remember, farming is cyclical. We are bound to see these type of opportunities again. Be prepared!

9 - Review objective yield, satellite, and weather data

There isn’t much to dive into under this topic other than actively trying to seek out objective data on the quality of the opportunity. It may not be readily available but you should seek it out.

This objective data helps fight the biases that I often talk about.

10 - Complete a five-year equipment projection

As I’ve talked about a lot, the main benefit of adding land to your operation is the ability to spread fixed costs out over a higher amount of revenue. This is a powerful way to grow your bottom line.

But….you need to be honest with yourself when evaluating your equipment expenses.

More acres = more depreciation + more repairs

I feel that you should conduct annual equipment “audits” on your farm. And these audits shouldn’t focus solely on the market value of your equipment but they should be part of a larger overall equipment “gameplan”.

When participating in board meetings while I worked at ShoreView Industries (a successful Minneapolis-based private equity firm), one of the most common discussions we had was around capital expenditures. These decisions were carefully planned out with the goal of optimizing the productivity of each business.

I can tell you what wasn’t discussed, “We had a great year! Let’s get our taxable income down as low as possible. Buy, buy buy!”. CapEx was well planned.

I think farmers should apply the same structured thinking to their asset allocation. It obviously doesn’t make sense to pay a burdensome amount of taxes. But we need to realize that during times of increased profitability, the farm-related assets you buy are likely inflated in price.

Instead of basing CapEx decisions around profitability and tax avoidance, let’s look at them with the goal of maximizing the farm’s productivity. With that in mind, we’re working on a new tool to aid in this process.

We’re going to apply structure to asset allocation decisions (specifically CapEx) by applying them to a Gantt chart. Gantt charts are typically used in project management to ensure timely completion of a project (that’s the goal anyway!).

We can use this structure to plot out the following information on your equipment.

- Hours at purchase

- Hours/year

- Targeted hours to trade/retire

- Estimated annual repair cost per piece of equipment

- Estimated amount “to boot” or net purchase price

Two valuable data points would come out of this.

- Estimated trade-in dates

- The cash flow-impact of equipment decisions (repair & acquisition)

The goal of this analysis is to allow you to conduct scenario analysis around different equipment acquisition strategies (eg. lease vs. buy, etc) and timing.

If you have a plan for when to make purchases of certain equipment, you can study the equipment market thoroughly and try to find the best deal possible.

When it comes to adding land to your operation, you don’t want to run into any cash flow landmines!

And two big ones can come in the form of:

- Large equipment repairs

- Equipment replacement.

Any plan is better than no plan, farm equipment decisions included.

11 - Complete a logistics analysis

One of the final steps to consider when evaluating a new land opportunity is how it factors into the current logistics of your farm.

Here are the factors I’d include in this logistics analysis. Note: these are all obvious but you need to consider the financial ramifications of each.

- Planting/harvest/spraying capacity

- Drying capacity

- Storage capacity

- Labor capacity

- Let’s assume you have storage capacity for 80% of your current production. If you add any acreage without adding storage, you’d obviously have to either rent/build storage or deliver at harvest.

We’ve had opportunities nearly every year to sell profitable prices for harvest delivery (typically via forward contracts) so there’s nothing wrong with moving your commodities to a buyer at harvest. You’ll just need to include the impact of drying and shrink on the net price used in your projections.

You also need to be honest with yourself about your price assumptions. If you are used to contracting your crop for a post-harvest delivery period, be sure to include the harvest delivery assumptions in your analysis (basis, drying, shrink, etc.).

I prefer a proactive grain marketing approach, especially with bushels that have a shorter marketing window (harvest delivery bushels).

So, just be honest with yourself when it comes to the grain marketing assumptions you are using in your analysis.

As we talked about previously…..if you run out of planting/spraying/harvest capacity, the cost of hearing out that work can easily negative the benefit of the added revenue and gross margin.

Finally, the worst outcome of adding land is if you end up not doing as good of a job as possible of farming your current farms. Missing a key harvest or planting window due to an increase in farm size can easily take away any advantage of adding the land.

But you know this, so it’s on to the final point!

12 - Use Common Sense!

At the end of the day, gains in farming typically come with at least some risk.

Your job is to analyze the financial impact of any opportunities you’re presented with the goal of truly understanding how they impact your bottom line. With that visibility, you can begin to identify and minimize any risks you face from either a yield, price, or cost standpoint.

Adding land is a powerful mechanism for growing your profitability and equity.

Seek opportunities but don’t fly blind!

If you’d like to try a free trial of Harvest Profit’s farm management software to help you with this analysis, sign up for a no-obligation free trial below.

Sources from above:

(1) Ola Svenson, ‘Are We Less Risky and More Skillful than Our Fellow Drivers?’, Acta Psychologica, 47 (1981), 143–51.

(2) Marc Alpert and Howard Raiffa, ‘A Progress Report on the Training of Probability Assessors’, in Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases, ed. by Daniel Kahneman, Paul Slovic, and Amos Tversky (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982).

(3) Daniel Kahneman, Thinking Fast and Slow (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011).

Nick Horob

Passionate about farm finances, software, and assets that produce cash flow (oil wells/farmland/rentals). U of MN grad.